| RECENT POSTS DATE 1/14/2025 DATE 1/2/2025 DATE 12/31/2024 DATE 12/26/2024 DATE 12/24/2024 DATE 12/18/2024 DATE 12/17/2024 DATE 12/14/2024 DATE 12/12/2024 DATE 12/12/2024 DATE 12/8/2024 DATE 12/8/2024 DATE 12/7/2024

| | | JESSE PEARSON | DATE 7/29/2015We’re all pretty much walking through a fine but pervasive mist of cultural nostalgia every day now. It’s exhausting living in the past, the present, and—depending on how tech-reliant you are—the future all at once, so I’m grateful when a small, digestible chunk of high-quality “remember when” comes well-packaged with a laser-focused agenda. Such is the case with No Problem: Cologne/New York 1984-1989, the book companion to an ambitious group show that ran at David Zwirner Gallery from May 1 - June 14, 2014. David Zwirner, son of the adventurous Cologne art dealer Rudolf Zwirner, whose gallery occupied the ground floor of the Zwirner family home during David's childhood, has run his New York operation since 1993. Now in his early fifties, he's since become one of the most powerful people in the global art juggernaut. But that’s okay, because Zwirner is one of the good ones, with great taste, intelligence, and a subtle sense of humor.

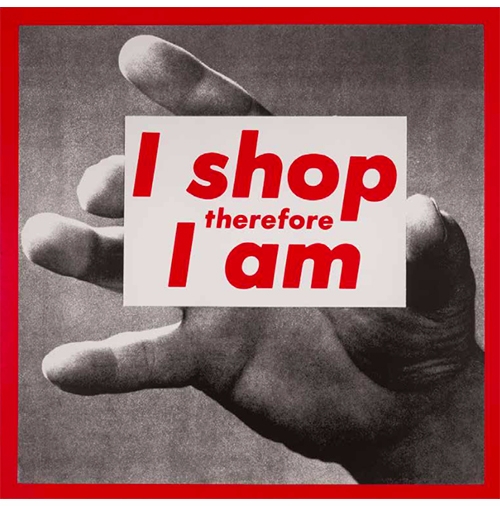

ABOVE: Barbara Kruger, "Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am)" (1987).

What we have in No Problem is a collection that links the kissing-cousins art worlds of New York and Cologne during a brief but incredibly vibrant five-year period at the end of the greedy, gutting, glorious 1980s. No Problem finds very real links between the personalities, aesthetic concerns, and lifestyles of artists working in cities that, though 3,700 miles apart, were undergoing the same fantastic collision of big-money collectors and low-rent artists, gutters and skyscrapers, etcetera. Twin hothouses for really good, really heady art, basically. The book includes work by Peter Fischl/David Weiss, Robert Gober, Jenny Holzer, Mike Kelley, Martin Kippenberger, Jeff Koons, Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, Raymond Pettibon, Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, Rosemarie Trockel and more. It’s fun to see these semi-early days of so many soon-to-be major artists put together in a new way here, and the selection succeeds in recontextualizing certain works, which is one possible noble goal of a group show.

ABOVE: Cindy Sherman, "Untitled 155" (1985).

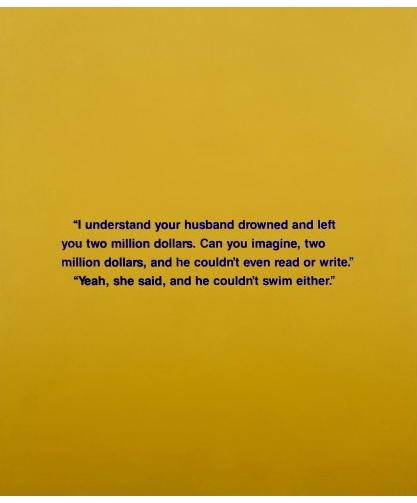

The Cindy Sherman photos included here, for example, benefit mightily from the context. Sherman's late-80s images of grotesque fuck-dolls, dirt, flora and synthetic pimples work in a very different way in the linear narrative of her own career than they do in No Problem: Cologne/New York 1984-1989, where they appear in between Richard Prince’s classic joke paintings and Spiritual America work and a beautiful selection of Mike Kelley’s do-it-all hippie-death sublimity.

ABOVE: Richard Prince, "Can You Imagine" (1988).

Sherman’s later-80s photos, in this mix, reveal more of their hysteric humor—the gory, funny scream—and less of the saturated, overwhelming gloom that I, for one, used to find in them. It’s cool how removing a segment of an artist’s work from its usual continuum totally changes the nature of the work.

ABOVE: Installation view featuring works by Mike Kelley.

As for the aforementioned Mike Kelley: any chance to take in his art is a welcome treat. Here we get a surprising group of paintings, drawings, stuffed-animal tubes and the truly wonderful patchwork bedding piece "Orphic Mattress" from 1989, which functions as a dayglo Rorschach test, a melted-crayola murder scene and a pure color-kick all at once. God, I love Mike Kelley.

ABOVE: Jeff Koons, "Buster Keaton" (1988).

The highlight of the Jeff Koons section is "Buster Keaton" (1988), which is a really special—probably my favorite—representative of Koons’ life-size Hummel figurine work. The tragic look on Keaton’s face—one of the greatest faces in the history of faces——as he stands astride a pony with a cartoon bird on his shoulder and surveys the trail before him is gut-wrenching, even in a photograph. I’ve never seen this piece in real life, but I’m pretty sure I’ll have to spend a couple of hours with it when I finally do. This isn’t the Koons that elevates the banal to the monumental—it’s the Koons who amplifies the sadness inside kitsch, which is a totally different and more difficult thing to pull off.

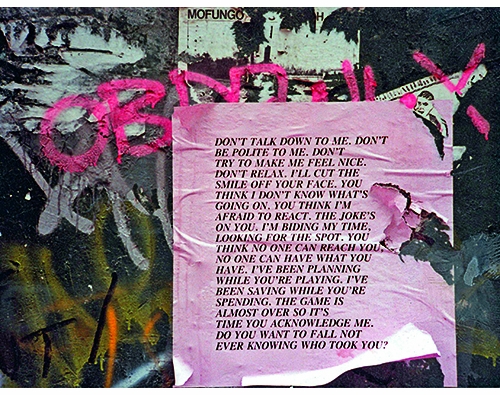

ABOVE: Jenny Holzer, poster from "Inflammatory Essays," New York, circa 1982.

Jenny Holzer’s text works—both in LCD scroller screens and on paper, have acquired more anger and punch as they’ve aged. That’s probably a harsh reflection on the fact that much of the patriarchal culture shit-show she was responding to in the 80s is still alive and kicking—if not even more powerful—today. In No Problem, seeing a piece from her "Inflammatory Essays" work photographed in situ on a graffiti covered wall brings to the forefront its inherent whiff of punk rage; it makes the “real” graffiti tags around it feel like mere decorative vanities.

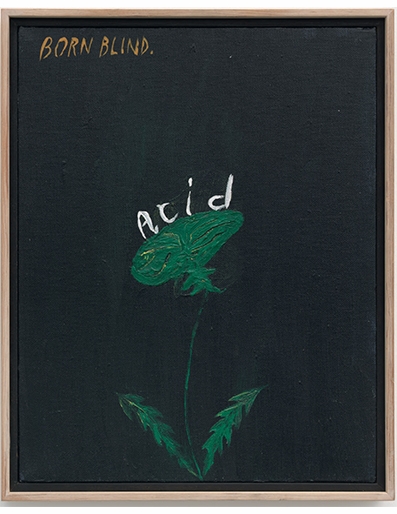

ABOVE: Raymond Pettibon, "No title (Born blind...)" (1990).

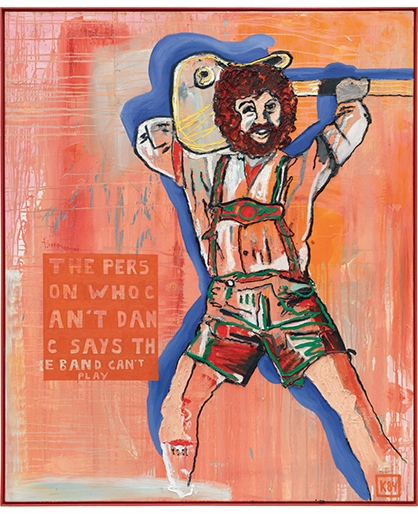

Also revelatory here are the Raymond Pettibon selections, particularly "No Title (Born blind…)" and "No Title (CCCP Sputnik cosmo…)", both 1990. With their all-over blackness and relatively simple pictorial action, they feel like a different sort of distillation of Pettibon’s common themes (such as hallucinogens and history) than we find in the bulk of his work. They also highlight, along with much of the art in this book, notably Martin Kippenberger’s joyous, hilarious painting "The person who can’t dance says the band can’t play" (1984), the obsession with 1960s counterculture among the hippest 1980s artists. These links of strychnine coated, Manson-and-Altamont worshipping, hippie-omega detritus informed so much of the best art and music of the 80s. It’s only fair that it get represented in No Problem.

ABOVE: Martin Kippenberger, "The person who can't dance says the band can't play" (1984).

If the cycles of nostalgia can be predicted like the path of a comet, I’m betting that No Problem foretells a major return of this 60s-via-80s vibe among young artists now (we already see it bubbling in the work of people like LSD Worldpeace, a.k.a. Joe Roberts, for example) and the righteous and unashamed political anger of prime-era Holzer and Barbara Kruger. I just hope that, like the best of these artists of the 80s, the kids today remember that homage and incorporation are good, but parroting and the stylistic steal… not so much.

JESSE PEARSON is a writer and the founder and editor of Apology magazine and a contributor to numerous other books on our list.

| |

|