| RECENT POSTS DATE 2/1/2025 DATE 1/31/2025 DATE 1/20/2025 DATE 1/18/2025 DATE 1/18/2025 DATE 1/16/2025 DATE 1/15/2025 DATE 1/14/2025 DATE 1/14/2025 DATE 1/9/2025 DATE 1/6/2025 DATE 1/3/2025 DATE 1/2/2025

| | | CORY REYNOLDS | DATE 7/16/2013

Below is Pritzker Prize-winning architect (and founder of both Morphosis Architects and SCI-Arc) Thom Mayne's Foreword to Greg Goldin and Sam Lubell's highly anticipated compendium of unbuilt visionary architectural plans for the city of Los Angeles, Never Built Los Angeles.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES: LOS ANGELES

By Thom Mayne

The built environment of Los Angeles has always exhibited a split personality of presence and potential. Branded as a tabula rasa on an urban scale, L.A. is a heterogeneous city of immigrants governed by a dispersed, fluctuating center of authority. It has an open-ended culture that constantly emerges to overturn its own past and future. During the past 100 years, the city has cultivated an architectural practice parallel to this identity of flexibility and reinvention, in which designers have found themselves united by an understanding of innovation as an engine of transformation. Yet this conversation––which has evolved as Los Angeles itself has grown––is often out of sync, projecting to an international audience while remaining inaudible on a local level.

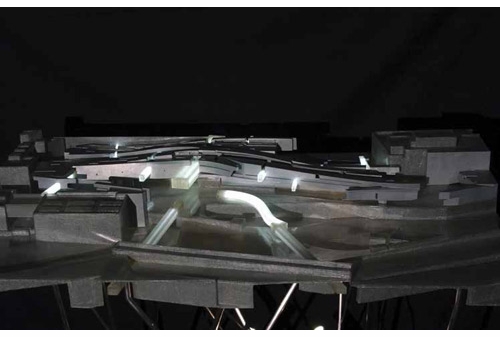

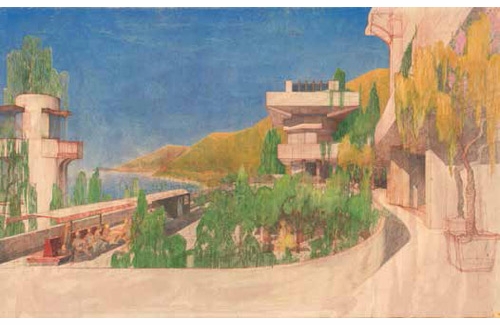

ABOVE: Morphosis's plan for LACMA, 2001.

Los Angeles’s relationship to its architecture is unique among major American metropolitan centers, characterized by a laissez-faire environment that has afforded incredible experimentation in the private sector. Commissions have largely come at the behest of a small group of idiosyncratic clients––quirky but not necessarily wealthy––who have supported provocative projects on a domestic scale. Public architecture, with a few exceptions, has been similarly dependent upon individual donors and their personal agendas rather than being generated out of the interconnected institutional framework that supports civic architecture in New York and other established American cities.

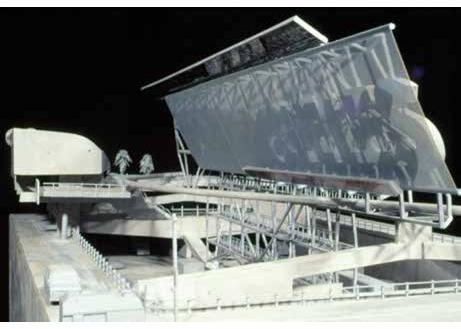

ABOVE: Morphosis's 101 Pedestrian Bridge, a connector between the Civic Center and the Los Angeles Plaza, over the 101 Freeway, 1998.

The radical practice that has grown here has seen four major iterations, but its origins are quintessentially L.A. in their eclecticism, launched from a dialogue between two native Austrians––Rudolph M. Schindler and Richard Neutra––in a foreign city. Modernist architect Adolph Loos had advised Schindler, then a student, to pursue work outside Vienna, which at the time was pervaded by a growing conservatism. In 1914, Schindler came to the United States to work with Frank Lloyd Wright, who brought him to Los Angeles to oversee construction on the Barnsdall House. Neutra and his wife, Dione, followed in 1923 and joined Schindler and his wife, Pauline, in the Kings Road House, which Schindler designed as an experiment in communal living. The mild climate and radicalized underground made Los Angeles an ideal laboratory for ideas that these architects transplanted from the intellectual avant-gardes in their home country. Both came with very European, modernist aspirations; and while these concepts were tolerated in residential construction, they proved too strange and too foreign to catch on in the public imagination of a still relatively provincial city. For instance, Neutra’s Lovell House (1927–29), with its unprecedented reconsideration of domestic space, predates Le Corbusier’s game-changing Villa Savoye (1928–31) yet remained relatively unsung and never led to bigger public commissions.

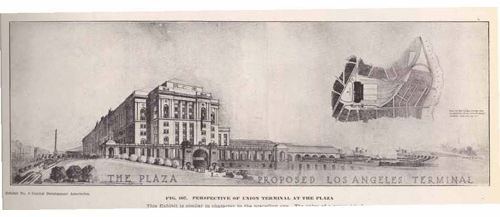

ABOVE: Proposal by the Central Development Association for Los Angeles's Union Station, 1918.

With the launch of John Entenza’s Case Study House program in 1945, architects started to expand the residential-scale experiments of a few iconoclastic individuals into a coherent program aimed at transforming the realities of everyday living. Supported by a revamped magazine, Arts & Architecture, a current was developing in Los Angeles that linked the city with the broader modernist project, despite the lag in civic support.

By the 1960s, young architects of my generation perceived an exhaustion of the problems of modernism and challenged the reductionist agenda through new questions advancing complexity and hybridization. With the founding of UCLA’s architecture program in 1968 and SCI-Arc in 1972, the architectural discourse in Los Angeles experienced an enormous acceleration, corresponding with the city’s growth from a provincial town into a major metropolis of international influence. As the city still lacked an ongoing public dialogue about architecture and urbanism, schools now became the main forum for exchanging ideas, facilitating a powerful conceptual camaraderie that allowed up-and- comers to break from their intellectual predecessors in a major way.

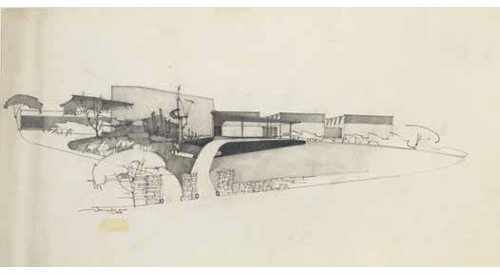

ABOVE: Richard Neutra's proposal for a Museum of Contemporary Art, Westwood, 1936.

As possibilities shifted in the nineties with the advance of digital work environments, Los Angeles continued to play host to vanguard ideas, with a new wave of designers exploring nonlinear progressions in form and knowledge through more fluid approaches to site and context. On the international stage, Los Angeles gained a reputation as an inexhaustible source of breakthroughs in design and urban planning. As an architectural culture, our identity was evolving; we were no longer mere experimenters on a domestic scale but now major exporters of creative capital. And, continuing the tradition of important ideas being implemented outside the local public arena, architectural practice in Los Angeles expanded to large-scale civic work, though not in our own backyard.

People love to portray the freedom of L.A.’s pluralism as a strength; in reality, it goes hand in hand with the city’s distinct failure to collectively embrace communal projects. That pluralism, combined with the lack of an ordering center, has prevented the cohesion necessary for rigorous architecture to take root in the civic sphere. Instead, the huge amount of talent in this city is being put to use on architectural projects globally and, except in rare instances, has played little role in shaping our public environment.

ABOVE: Fred Lyman's vision of a Malibu Monorail.

The real missed opportunity of Los Angeles, then, lies in the loss or displacement of intellectual creative capital that has occurred as our architects move on to other cities, other countries, other opportunities. The treasure trove of innovation contained in this book attests to a history of latent, untapped potential, yet the message of these unrealized projects is one of not only regret but also optimism. In considering Never Built Los Angeles, we see that our city clearly still holds its original promise––that there remains unfinished space here to transform and build.

Metropolis Books

Hbk, 11.5 x 8.5 in. / 376 pgs / 200 color / 200 b&w.

| |

|