| RECENT POSTS DATE 12/11/2025 DATE 12/8/2025 DATE 12/3/2025 DATE 11/30/2025 DATE 11/27/2025 DATE 11/24/2025 DATE 11/22/2025 DATE 11/20/2025 DATE 11/18/2025 DATE 11/17/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/14/2025

| | | CORY REYNOLDS | DATE 10/24/2014In today's New York Times, Karen Rosenberg praises the Philadelphia Museum's "elegant and convincing reappraisal" of this defining figure in twentieth century photography. For those who can't make it to Philadelphia (and even those who can), we recommend the new, expanded edition of Aperture's classic monograph, which contains an introduction and image-by-image commentary by Peter Barberie, curator of the Philadelphia retrospective. Below are a selection of images from the book, alongside Barberie's captions.

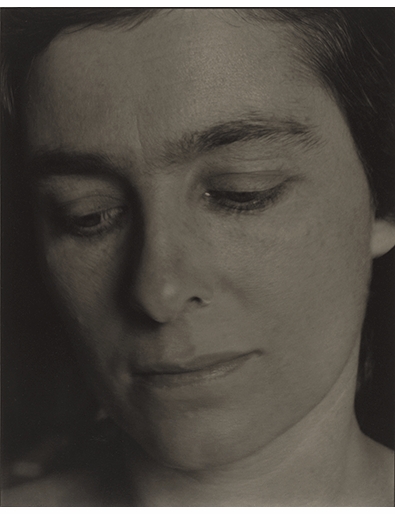

Rebecca, New York, ca. 1921

In 1919 Strand began experimenting with a large-format view camera, and by 1921 it was his chief instrument. This represented a fundamental change in his work: he now exclusively made contact prints the same size as the 8-by-10-inch negatives, bringing a clarity and sharp focus that he would come to view as essential to photography. At this time he began to photograph his new love, Rebecca Salsbury, whom he would marry in 1922. Undoubtedly influenced by Stieglitzís contemporaneous portraits of Georgia OíKeeffe, which he deeply admired, Strandís portraits of Rebecca are nonetheless a distinct achievement. When making them he was motivated by the important problem (in his thinking) that photography is art made with a machine. The Rebecca pictures, of which this is one of the most tender examples, suspend the cameraís cool objectivity in marvelous tension with the vital subjective presence of both model and artist.

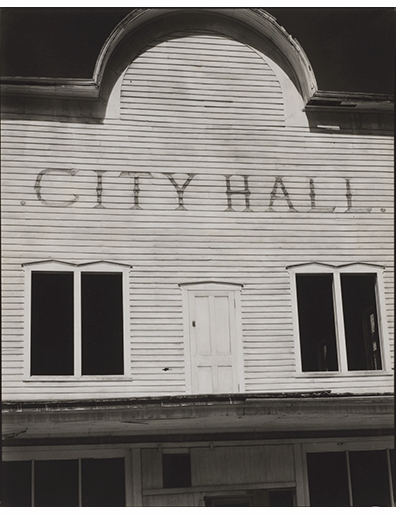

City Hall, St. Elmo, Colorado, 1931

Strand made multiple photographs of this city hall in a Colorado ghost town. He was fascinated by its role as a symbol of civic order imposed on what he imagined as the unruly frontier. (St. Elmo had been a gold mining town founded in the 1880s.) This photograph of the building is made stranger than the others by its tilted composition and cropped view of the structureís lower story, which succinctly conveys the sceneís deserted nature and past life. One can imagine the mayor or sheriff of St. Elmo emerging through the door to address the populace from his elevated stage.

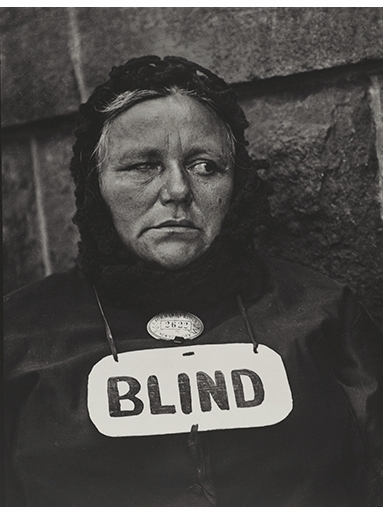

Text appears infrequently in Strandís photographs. When it does, it is typically in the form of sparse, emblematic signs announcing an important quality of the subject, as in this view or his earlier photograph "Blind Woman, New York." In both Strand uses vantage, cropping, and scale to show us more than the words announce, so we sense the humanity of the blind peddler, and the character and history of this erstwhile civic building.

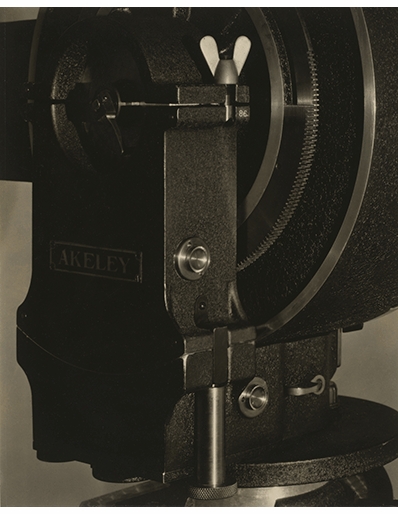

Akeley Camera with Butterfly Nut, New York, 1923

In 1922 Strand acquired an Akeley movie camera with the intention of producing commercial films for a living, which he did successfully for more than a decade. The Akeley was the invention of Carl Akeley, an adventurer and taxidermist who designed dioramas at New Yorkís Museum of Natural History and who wanted a film camera with the mobility to capture wild animals in motion. Strand loved the Akeley, in part because it was produced in a small shop in New York City by a handful of skilled craftsmen, putting a human touch on the machine age that he wanted to tackle in his art. Between 1922 and 1923 he used his view camera to make a small series of precise and elegant records of both it and the shop where it was made.

Blind Woman, New York, 1916

In 1917, a year after first publishing Strandís photographs in Camera Work, Stieglitz combined the journalís last two issues and devoted them entirely to Strandís newest work, including his abstractions and the anonymous street portraits he made in New York City. Among the eleven images Stieglitz published, "Blind Woman" is undoubtedly the most riveting because of the stark message emblazoned across the figureís chest. The woman stands against a granite wall; as viewers, we are so close that we have little choice but to observe her neat appearance under the armor of her sign, medallion (a peddlerís license), and heavy coat.

Woman and Boy, Tenancingo, Mexico, 1933

In Mexico Strand resumed making anonymous portraits, using a prism lens that was more sophisticated than the false lens he had used in 1916. Roaming the streets of towns and villages with his Graflex camera, he waited until people were accustomed to his presence. Sometimes they looked directly at the camera, watching Strand as he appeared to photograph another subject nearby.

Far from snapshots, these photographs take in details of textiles and other objects, and they often show figures in quiet moments, regardless of their public surroundings. In both subject and format they resemble the work of the pioneering Scottish photographers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, whose portraits Strand revered. His willingness to adhere closely to the work of earlier artistsóin a sense, to explore it fully from the inside out by making similar picturesóis a notable quality of his photography. Capable of piercing originality, he was uninterested in novel subjects or compositions for their own sake, whereas he was willing to work ever further into a formula or motif that he found successful.

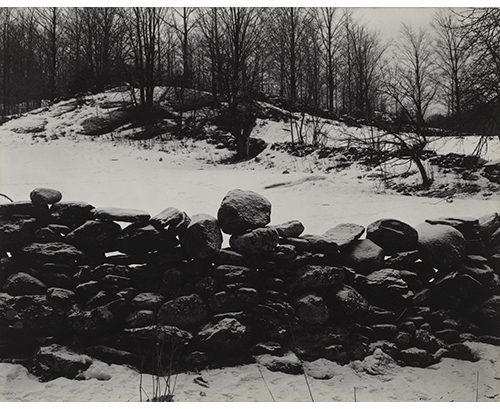

The Stone Wall, Stockburgerís Farm, East Jamaica, Vermont, 1944

If the elegant neoclassical buildings of New England formed a compelling subject for Strand, so did the hard, intractable materiality of the place. He shows us this portion of stone wall in contrast with the sinuous hillock beyond it. Snow and light define every rock, so that we see the labor of the wallís construction and comprehend the significance, at once modest and assertive, of its mark on the landscape.

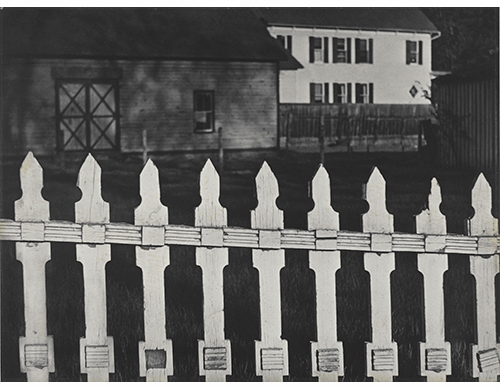

White Fence, Port Kent, New York, 1916

Strand continued to make abstractions in late 1916 and 1917, but he expanded the scope of the pictures to involve landscapes and urban scenes. He justly considered "White Fence, Port Kent" among his most complete statements on such abstraction. Not disorienting in the manner of his still-life experiments, it simply organizes the planes of the picture into divergent diagonal lines and basic shapes of white, black, and gray. But above all it is an unforgettable representation of the American homestead, viewed from a distance as if by an outsider, or by someone returning. Its concise arrangement of forms imparts all the brevity and power of a masterful short story.

Young Boy, Gondeville, Charente, France, 1951

The French author Michel Boujut wrote a poignant book tracing this young manís story. The wonder of Strandís photograph is that we do not need to know it. The boy stands before us, resentful with impatience and the certainties of youth. We are amazed at his beauty, and we fear that he does not understand his power. What can we do? Words would not help. He would not listen, and we can be no closer to him than we are in this photograph.

| |

|