| RECENT POSTS DATE 6/1/2025 DATE 5/10/2025 DATE 4/30/2025 DATE 4/26/2025 DATE 4/24/2025 DATE 4/23/2025 DATE 4/21/2025 DATE 4/17/2025 DATE 4/14/2025 DATE 4/10/2025 DATE 4/10/2025 DATE 4/8/2025 DATE 4/7/2025

| | | THE ORIGINAL COPY: MOMA EXHIBITION SITETHOMAS EVANS | DATE 8/11/2010Published for a show at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Original Copy proposes an intriguing corollary to Mallarmé's famous dictum that "everything in the world exists in order to end up as a book": that all sculpture exists to end up as a photograph, that this fact affords a further creative-interpretive occasion and that the photographing of sculpture constitutes its own hitherto unidentified genre within both photography and sculpture.

Photography has of course proved to be the final condition of numerous lost or destroyed artworks, but here, MoMA curator Roxana Marcoci, who has conceived the book and accompanying show, describes a deeper collaboration between photography and sculpture, in which the photograph allows the sculpture to be performed and dramatized in ways that simply exhibiting the sculpture, in 'real time' and 'real space,' doesn't permit.

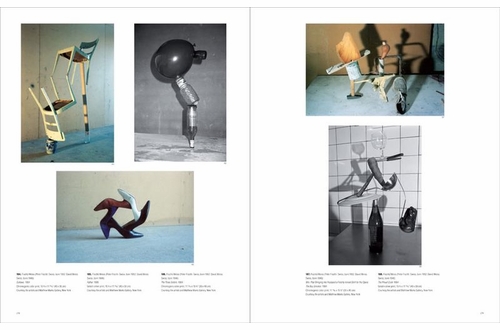

What does this photographic 'performing of sculpture' entail? Frequently, it entails a defusion of the object's spatial neutrality (so enhanced by exhibition and museum display) into a stage that is not the world, but the world rendered as theater. Attaining this shift in object status, sculpture can then ostensibly move among the world's objects, but operating parenthetically like a toy, or a body part, or a tool enabling or collaborating with moving bodies; and perhaps more importantly, it can begin to at least invoke the atmosphere of a temporality and duration in which the object participates, recorded in the photographic instant.

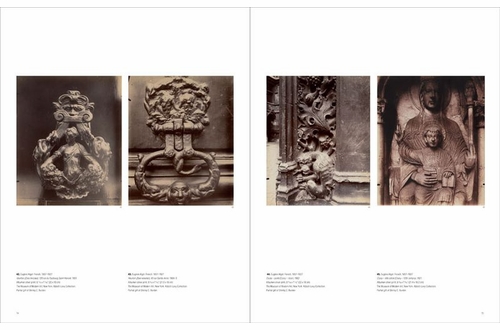

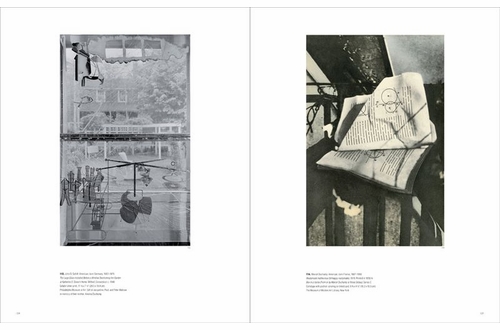

This collaboration dates back to the earliest days of photography, for sculpture offered an advantage over more mobile subjects--being stationary, it suited the then-lengthy exposure times of nineteenth-century technology. As a result, Marcoci notes in her introduction, "by the later nineteenth century, highlighting a sculpture's most interesting details through the use of close-ups and enlarged photographs of areas normally inaccessible to the average viewer became increasingly popular." Accordingly, the earliest images in this book are nineteenth-century dramatizations of ancient Greek, Roman and Egyptian sculpture, usually executed for museological/anthropological purposes, but already producing a new kind of two-dimensional sculptural content from three-dimension information. Pursuing this theme into the streets of Paris at the century's close is Atget as reproduced on the pages of the book above.

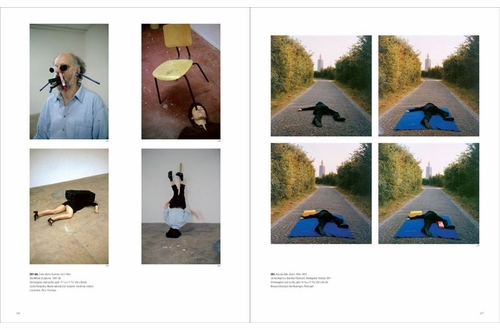

The case study that perhaps most usefully illuminates the scope of Marcoci's conception in The Original Copy is that of Marcel Duchamp. Almost every one of Duchamp's major works yielded some new and enlarged incarnation as a photograph, from the urinal (whose famous and dramatic depiction by Stieglitz is the sole surviving documentation of the work), to the portraits of Duchamp posing with works such as "The Bride Stripped Bare," to the reduction of his oeuvre to photographic reproduction for the "Box in a Valise," to the recording of ephemeral works such as the "Unhappy Readymade" depicted on the right:Duchamp stands at the head of a long parade of twentieth-century artists interacting with, wearing or in some way elaborating their sculptures: Giacometti (as portrayed by Cartier-Bresson), Hans Bellmer, Eva Hesse (as photographed by Herman Landshoff), Andre Cadere, Joseph Beuys, Yayoi Kusama and others. If this mini-genre can be seen as an extension of, or peek into, the character of studio practice, or an insertion of the author into the numinous field of the artwork--"I made this!"--one can also point to the curious negation of authorial hand that it effects through the artifice of performance, as everything implicated in the picture frame gets leveled to a sculptural presence.

From the above rollcall of artist-performers, we might single out Eva Hesse for bringing conscious strategy to the occasion. Hesse, who commissioned and directed Landshoff's 1968 photoshoot, performs the rich implications of her sculptures as garment, as fetish and as household object, often with a warmly wicked smile that undercuts the potential authority of those implications.

In fact the photographic portrayal of sculpture frequently leads to moments of humor and play: think of the slapstick of Fischli & Weiss's Equilibres sculptures, Louise Bourgeois' mischievous expression with underarm phallus in Robert Mapplethorpe's classic 1982 portrait and Erwin Wurm's One-Minute Sculptures (all of these are included here). In the example of Wurm and Fischli & Weiss, one notes that the sculpture existed only for the moment at which it was photographed: Wurm's actors presumably ceased their absurdist poses once the performance was photographed, and Fischli & Weiss' delicately balanced bric-a-brac likewise collapsed (that is, unless it was all glued into place). While the introduction of temporal determination into sculpture is not necessarily predicated upon photography's role, the viewer's heightened consciousness of the moment grasped and gone endows the photograph with a thrilling tension.The dramatization of object by artist inevitably leads to performance by/of body alone, and in photographs of Valie Export, Yves Klein and Yvonne Rainer, the pressing, casting and placing of bodies into space gains sculptural pull through photography's agency. Here again, the body as author is transmuted into a body of great plasticity, sculpting its way into space as something more than sentient but other than individual or possessed of personality. All of these themes and others besides are indicated by the book's chapter titles, which merit listing tas an elucidation of its scope:

I. Sculpture in the Age of Photography

II. Eugène Atget: The Marvelous in the Everyday

III. Auguste Rodin: The Sculptor and the Photographic Enterprise

IV: Constantin Brancusi: The Studio as Group Mobile and the Photos Radieuse

V. Marcel Duchamp's Box in a Valise: The Readymade as Reproduction

VI. Cultural and Political Icons

VII. The Studio Without Walls: Sculpture in the Expanded Field

VIII. Daguerre's Soup: What Is Sculpture?

IX. The Pygmalion Complex: Animate and Inanimate Figures

X. The Performing Body as Sculptural Object

The Original Copy surveys a huge range of work across these chapters, but every reader will think of further chapters and themes to add, so rich is its conceptual suggestiveness. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Hbk, 9.5 x 12 in. / 242 pgs / 120 color / 180 b&w. $55.00 free shipping | |

|