| RECENT POSTS DATE 12/5/2024 DATE 11/21/2024 DATE 11/16/2024 DATE 11/13/2024 DATE 11/11/2024 DATE 11/9/2024 DATE 11/7/2024 DATE 11/6/2024 DATE 11/6/2024 DATE 11/5/2024 DATE 11/3/2024 DATE 11/2/2024 DATE 11/1/2024

| | | ADAM JASPER | DATE 9/15/2010For a brief period at the end of the nineteenth century, Louis Wain was arguably England’s most reproduced artist. Not England’s most lauded artist, certainly—there are no works by him in the National Gallery, for example—but between 1895 and 1905 some forty books illustrated by Wain appeared on the market, alongside hundreds of postcards, miniatures, mementos, and keepsakes. All of them feature the same subject matter: funny cats. Cats playing golf, cats taking photographs, cats in bow ties or doffing bowler hats.

A pre-insanity Wain drawing, assuming cats playing poker is not insane.

The Louis Wain cat was inquisitive, upper middle class, bright-eyed, and boisterous. He walked upright on his hind legs, wore clothes, used tools, and, although prone to mishaps, had a keen sense of propriety. The Louis Wain cat was not, in short, a cat, but a typically extroverted Edwardian gentleman. “When I was young,” said Wain, “no public man would have dared acknowledge himself a cat enthusiast; now even MPs can do so without danger of being laughed at.”

Wain first achieved notoriety in 1886 with a Christmas supplement to the Illustrated London News, a narrative drawing called “A Kittens’ Christmas Party.” The image took Wain eleven days to draw, featured over two hundred felines, and ran across a full two pages of the newspaper. That it was printed as a spread is significant; everything not pertaining to Wain’s cat tableau was thereby omitted from the page, creating catland as a humane world free of humans, a kind of virtual utopia. H. G. Wells wrote, “He invented a cat style, a cat society, a whole cat world. English cats that do not look like Louis Wain cats are ashamed of themselves.”

The craze for anthropomorphized adorables is not entirely unfamiliar. In its weakness for the cute, the twenty-first century shares characteristics with the end of the nineteenth, and just as a significant proportion of Internet traffic today is devoted to pictures of baby animals, there soon emerged in Edwardian England a veritable industry dedicated to publishing Wain’s anthropomorphized cats. “A Christmas without one of Louis Wain’s clever catty pictures,” Frances Simpson wrote in The Book of the Cat (1903), “would be like a Christmas pudding without currants.” On the strength of his anatomically implausible caricatures, Wain was eventually elected president of England’s National Cat Club.The craze for anthropomorphized adorables is not entirely unfamiliar. In its weakness for the cute, the twenty-first century shares characteristics with the end of the nineteenth, and just as a significant proportion of Internet traffic today is devoted to pictures of baby animals, there soon emerged in Edwardian England a veritable industry dedicated to publishing Wain’s anthropomorphized cats. “A Christmas without one of Louis Wain’s clever catty pictures,” Frances Simpson wrote in The Book of the Cat (1903), “would be like a Christmas pudding without currants.” On the strength of his anatomically implausible caricatures, Wain was eventually elected president of England’s National Cat Club.

Wain’s preoccupation with cats had its origin in 1883, when, as a junior commercial illustrator of no particular prominence, he had begun to draw his wife’s pet, a black-and-white kitten called Peter, to amuse her. She had been diagnosed with breast cancer and confined to her bed. Peter became her chief companion, Wain’s muse, and a distraction that culminated in an obsession for the artist. Upon Emily’s death three years after her confinement, Wain allegedly claimed that Peter became the vessel of at least a portion of Emily’s soul.

Whether the inception of his illness can be traced back to this experience or not, Louis Wain is now chiefly known for the pictures he created during his subsequent descent into schizophrenia. During the 1890s, he began to make “scientific” observations that he initially expressed with decidedly Victorian eccentricity: “Strangely enough, I once had the impression that a cat’s tendency was to travel north, and to face north as a magnet does, and that this tendency had some intimate association with the electrical strength of its fur.” Wain was unable to negotiate effectively to protect the royalties from his work; moreover, the price of his pictures began to decline, in part due to over-supply. World War I ruined him: funds foolishly invested in inventions, a shipload of futuristic porcelain cats torpedoed on the way to the US, and a general loss of interest in Edwardian pastimes all combined to render Wain destitute.

As his poverty deepened, his concern over the effects of electricity became a terror. After he violently attacked one of his sisters, he was taken to the pauper’s ward of Springfield Hospital in Tooting on 16 June 1924.

It was in the pauper’s hospital that Wain encountered an English bookseller by the name of Dan Rider, whom he met while the latter was undertaking one of the semi-charitable, semi-voyeuristic visits to asylums that were once a typical activity of the middle classes:

I was on a committee that had to make a number of visits to asylums. During one of those visits, I was passing up and down a corridor when I noticed a quiet little man drawing cats. I went to inspect his work. “Good Lord, man, you draw like Louis Wain.” “I am Louis Wain,” replied the patient. “You’re not, you know,” I exclaimed. “But I am,” said the artist, and he was.

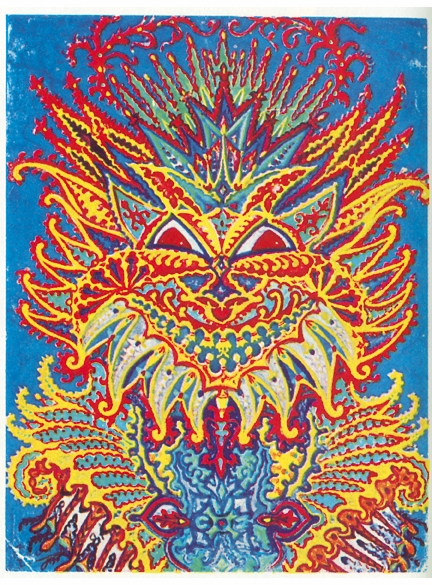

In a subsequent appeal for funds to help Wain, British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald personally intervened, recalling how Wain had been “on all our walls fifteen to twenty years ago.” He went on to attest that “probably no artist has given a greater number of young people pleasure than he has.” In the meantime, Wain was drawing pictures that were increasingly unlike those the prime minister fondly recalled. A work made by Wain sometime after his institutionalization in 1925. Although the exact dates of these works are not known, some of them have been sequenced in psychology textbooks to demonstrate the progressive dissolution of the image in a psychotic breakdown. This analysis was first proposed by Bethlem Hospital psychiatrist Dr. Walter Maclay, who had himself engaged in early experiments in the effects of mescaline on visual perception.

In a set of images that is now often used as a textbook demonstration of the optical effects associated with psychosis, we see a progressive dissolution not unlike that of Lewis Carroll’s disappearing Cheshire Cat (and it is noteworthy that Carroll also suffered severe migraines and associated hallucinations). These were not the only types of images, however, that Wain was capable of creating in his later schizophrenic period. Even in the years leading up to his death in 1939, he produced his typical comic scenes of cats playing various roles within the asylum: as doctors, psychologists, patients, and orderlies. All the same, it is for his distorted images that Wain is best remembered. They display a kind of luxuriant ornamentality that was ascribed to schizophrenic art in general by German psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn in his epochal Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (Artistry of the Mentally Ill) of 1922. Prinzhorn described such dense edge-to-edge work as motivated by a kind of horror vacui, as if the confrontation with the void was being fought out on paper.

In this famous sequence, the cat’s facial expressions become increasingly stunned and empty, or radiantly malevolent. These emanations are initially concealed in the background decoration, a kind of wallpaper that becomes gradually animated into a psychedelic kaleidoscope; the pictures begin to pulse with a constrained energy. (As Wain would title one work: the fire of the mind agitates the atmosphere.) Gradually, the wallpaper and the feline begin to merge into a single mandala. Arabesques spread out from and colonize the face of the cat with increasing density until only two floating eyes remain in the dead center of an infinite crystalline mosaic. Cabinet

Pbk, 7.75 x 9.75 in. / 112 pgs / 60 color / 40 b&w.

| |

|