| RECENT POSTS DATE 12/11/2025 DATE 12/8/2025 DATE 12/3/2025 DATE 11/30/2025 DATE 11/27/2025 DATE 11/24/2025 DATE 11/22/2025 DATE 11/20/2025 DATE 11/18/2025 DATE 11/17/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/14/2025

| | | CORY REYNOLDS | DATE 2/16/2012

The New York Times' Roberta Smith reviews Kippenberger: The Artist and His Families, Susanne Kippenberger's stupendous biography of her brother, published by J&L, this weekend in the Sunday Book Review. Below is a transcript of Smith's glowing review.

RULING THE ROOST

A German journalist looks at the impact her brother made as an artist.

By ROBERTA SMITH

The comet that was the German artist Martin Kippenberger streaked across the firmament for about two decades, excessively gifted, and also just plain excessive. By 1997, the restless, charismatic exhibitionist, multitasker and motormouth — a man with “no off switch,” as this book puts it — was dead, burned out at the age of 44 from a toxic combination of hard work and hard partying, both sustained by astounding quantities of alcohol.

To an extent that has few equals in late-20th-century art, Kippenberger drew equally and effortlessly from traditions of the skilled painter-draftsman, à la Picasso and Matisse, and the cool-handed manipulator of found objects and images, à la Duchamp. The harsh, irreverent body of work he left behind was enough for a career three times as long. It encompassed paintings, sculptures, collages, drawings, installations, photographs, books and prints, and mongreled styles from Expressionism and Dada forward, including Pop Art, Photo Realism, Neo- Expressionism, Social Realism and conceptual, performance and appropriation art. He staged numerous exhibitions, both of his own work and that of his contemporaries (which he assiduously collected), invariably parlaying the accompanying catalogs, exhibition announcements and posters into subversive exercises in their own right.

In Berlin in the late 1970s, Kippenberger managed S.O.36, a punk nightclub where he also regularly performed, sometimes by simply stealing the show from the scheduled acts. He played briefly in a band, cut a record or two and had minor parts in two movies. In Cologne, where he more or less ruled the roost during the macho, boom-time ’80s, he and his confreres, including the painters Albert Oehlen and Werner Büttner, were notorious for their “extreme artist-behavior.” Pants were regularly dropped; bar talk was a blood sport. (Büttner called his friend “a virtuoso at giving offense.”) But the tall, fair and handsome Kippenberger was also known as a dancer so inspired and gallant that women sometimes lined up to twirl around the floor with him. Throughout, he led a peripatetic existence, living and working in some 15 cities and other outposts around the globe, befriending hoteliers, restaurateurs, bartenders and maîtres d’hôtel in every port.

Martin Kippenberger in Venice, 1996.

In Kippenberger: The Artist and His Families, Susanne Kippenberger, the youngest of his four sisters, offers a tender, reasonably clear-eyed, oddly gripping account of her only brother’s headlong plunge through life. A journalist for a Berlin newspaper, she writes in a brisk, personable style that has been sensitively translated by Damion Searls, who has also done justice to Martin Kippenberger’s penchants for non sequiturs, malapropisms and skewed aphorisms (“Never give up before it’s too late”). She tries to keep the pros and cons of Kippenberger’s outsize personality in view, citing some of the most egregious examples of his art and behavior, but her sympathies are never in doubt.

She introduces him as “an anarchist and a gentleman” who “really was a child his whole life” and — nothing new where overachievers in the arts are concerned — “never felt sufficiently loved.” He “needed interaction the way others need solitude,” she writes of his almost complete inability to be alone. Wherever he went, he established a cohort of friends, collectors, dealers and fellow artists who were on call for nocturnal carousing, not to mention the prolonged birthday celebrations he liked to give himself. One close companion invented the word Zwangsbeglücker to describe his demanding sociability: someone who enforces “mandatory good cheer.” Friends sometimes found that sitting home with the lights out was the only defense against his unannounced visits. “Martin lived in Stuttgart for only six months,” Ms. Kippenberger writes dryly, “but it felt like years to many people.” The families of the book’s title encompass the informal ones that Kippenberger assembled around him as well as the real ones he insinuated himself into, usually those of wealthy patrons or well-placed girlfriends. But it is the rather wild and creative clan that produced him, and that Ms. Kippenberger knows firsthand, that is most affecting. It helps that they wrote good letters. In one, written when Martin, still a teenager, was responding well to drug rehab, his mother summed up her relationship with her son by describing herself as “a chicken that had hatched a duck, and now is clucking anxiously on the shore while the duck happily paddles around in the pond.”

As detailed here, Kippenberger’s childhood in Essen in the Ruhr Valley preordained to a startling degree the artist he became; there’s the same nonstop activity, the constant need for attention, even similar artistic habits. For someone adept at directing assistants in the making of his art, it seems relevant that his mother, Lore, wrote to a favorite children’s book illustrator asking her to draw a portrait of the family based on the brief enumeration of its members in her letter. (The illustrator complied, with a drawing that is reproduced in this book.) An account of the family yard, filled with sculpture, playground equipment and “an old, brightly painted BMW,” sounds a bit like a Kippenberger installation — forget that the exterior of the house was painted with images devised by an artist friend.

The impetus for most of the tumult was Gerd, the bossy, restless, competitive father, a coal-mine director, painter manqué and avid art collector, as well as a dedicated bon vivant and party organizer, as deft as his son would be at ad hoc toasts and speeches. Gerd was in many ways the original Zwangsbeglücker, whom Albert Oehlen described simply as “the extreme version of Martin” — a scary thought — which suggests his major role in the torment behind his son’s drinking. Martin dedicated “Through Puberty to Success,” one of his first catalogs, to his father with the revealing words “from whom I inherited my father complex.”

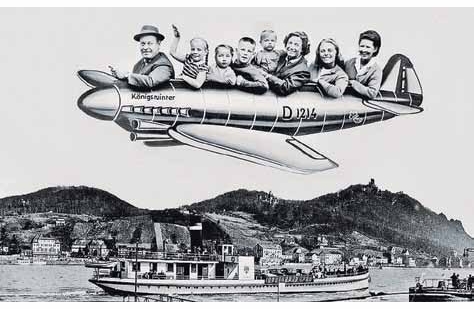

A souvenir photo from a Kippenberger family vacation: Gerd is in front, and Lore holds

a friend’s child; the author and Martin Kippenberger are third and fourth from the front.

This book reproduces virtually no Kippenberger art, but reveals instead a life devoted completely to it. Anything and everything was fodder for Kippenberger’s work, starting with childhood photographs and report cards. A 1985 sculpture made from wooden transportation pallets was partly inspired by the death of his mother, killed when a stack of them slid off a truck and struck her as she walked along the street. In 1989, when critics called him a “neo-Nazi playboy” and worse, Kippenberger responded with a life-size mannequin-like sculpture of himself facing into a corner, like a schoolboy being punished. (One version of the piece, titled “Martin, Into the Corner, You Should Be Ashamed of Yourself,” is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan and currently on view.)

Following her brother’s trajectory, Ms. Kippenberger’s text sometimes reads like an elaborately fleshed-out chronology, crowded with projects, collaborations, trips, inebriated pranks, the constant search for comfort food (noodles were big) and intermittent, decreasingly effective stints at spas for what he called his “Sahara Program” — or drying out. But because he was so productive and worked with so many different people — both artists and dealers — the story of his career also serves as a partial account of the German art scene of the 1980s and early ’90s.

Ms. Kippenberger provides wonderful thumbnail portraits of the many key figures in her brother’s life, while using their reminiscences to create a finely diced composite oral history that makes palpable both his charming and his repellent sides. (She interviewed some 160 people, all listed in the acknowledgments.) One fellow traveler remembers turning from watching the New Year’s Eve fireworks out the window of their rented high-rise apartment in Rio de Janeiro, to see Kippenberger waltzing with the housekeeper, as “one of the most emotional moments of my life.” In contrast, one guest called the three-day celebration of Kippenberger’s 40th birthday “torture.” His antics had grown tiresome, and his health was failing. He hadn’t given up, and it was too late.

Kippenberger would probably have agreed with Rimbaud, who recommended a “long, prodigious and rational disordering of the senses.” Unlike Rimbaud, he didn’t abandon his art after a few years; he worked to the end, devoting his last energies to a series of paintings, drawings and prints in which he assumed the different poses of the desperate occupants of Géricault’s great “Raft of the Medusa,” substituting his ravaged, bloated body for their emaciated ones with results that were both harrowing and parodic.

It may sound hackneyed to say that Kippenberger’s life was an extended alcohol- fueled performance piece, but in a sense it was — at once self-indulgent, self-destructive and, oddly, selfless, almost selfsacrificing. He enacted the artistic drive in the extreme, flirted consistently with failure, and in his manic, exaggerated, remorseless way, exposed the human vulnerability behind all great art. It was an intense, blinkered life, not all that different from that of the Abstract Expressionist painter Willem de Kooning, another nonstop drinker and incessant art maker, only much shorter and with a much larger supporting cast.

J&L Books

Hbk, 6 x 9 in. / 564 pgs / 25 b&w.

| |

|