| RECENT POSTS DATE 4/10/2025 DATE 3/31/2025 DATE 3/29/2025 DATE 3/29/2025 DATE 3/27/2025 DATE 3/27/2025 DATE 3/20/2025 DATE 3/20/2025 DATE 3/18/2025 DATE 3/16/2025 DATE 3/15/2025 DATE 3/14/2025 DATE 3/13/2025

| | | ERIN DUNIGAN | DATE 2/2/2011I think that this lost world––as it really is a world that is lost––it had its point of rest, its balance. -Ildico Jarcsek-Zamfirescu

Sifting through the library, the melancholy music of Mazzy Star faintly resounding in the background on another unsurprisingly rainy day; I am struggling to find inspiration. I am digging deep, trying to uncover a book that really hits a chord. Then suddenly, without thought or expectation, I reach in and pull out Beatrice Minda’s Innenwelt (or Inner World) and I have one of those utterly satisfying moments where I know instantly, THIS is exactly what I’ve been searching for.

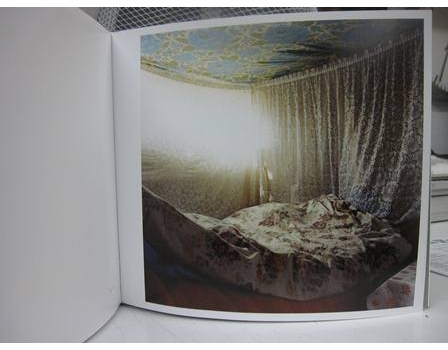

As I've recently seen Where the Wild Things Are, the stunning cover image brings to mind a cozy fortress of draped blankets, the kind every kid with a big imagination builds as their secret hideaway. Light filters through a window and suffuses the tableau with a warm and dreamy glow, heightening the magical ambiance. It is transformative. Blankets, sheets and lace curtains are draped everywhere, covering the floor, ceiling and walls. None of the patterns match but the blending of colors and textures manages to create a delicate, nearly vintage, chrysalid aesthetic. It’s a bit bohemian really and I just want to toss myself right into the center of that big fluffy blanket and snuggle into the sunlight. It’s easy for me to imagine myself inhabiting this space, especially considering the lack of persons in Beatrice Minda’s oeuvre. But as enjoyable as it is to project myself into this quietly enticing, atmospherically charged environment I must remind myself to stop and realize that I do not belong in this place. I am merely a voyeur peering into a private and intimate space: someone else’s bedroom.

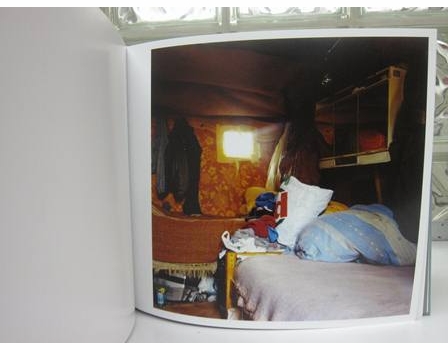

Upon reading the catalogue’s introductory essay, “On the Fading of Things” by Ulrich Pohlmann, I was struck by one particular observation: “The presence of those absent is part of the appeal of Beatrice Minda’s works, bringing insights into the inner life of the private sphere, which usually remains hidden.” The presence of those absent. Pohlmann also makes references to the work of Martin Parr and Gregory Crewdson in his introduction, both as photographers whom explore intimate interior scenes, as occupied by people, whether as a social critique or as a mise-en-scene construction. In contrast, the art of Beatrice Minda, a former pupil of Katharina Sieverding, portrays an overwhelming consciousness of absence, stillness, silence. It’s reminiscent of the booming silence a person projects when they have something on their mind but resist speaking. It’s the loudest silence imaginable.

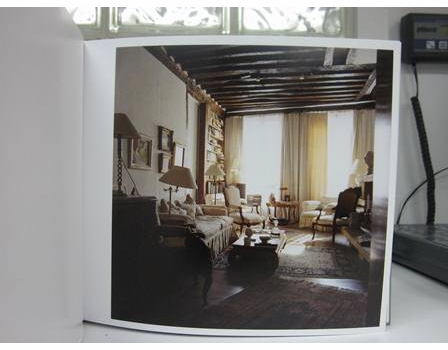

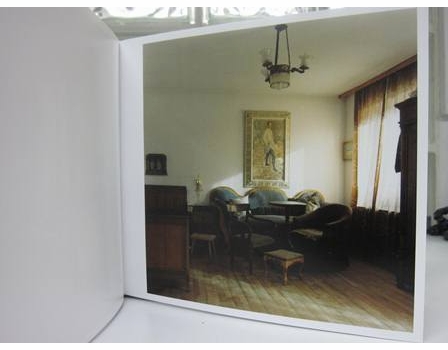

Innenwelt presents a series of “photographs of Romania and of exile.” Minda’s photographs document the apartments of Romanians in their homeland, as well as the abodes inhabited by exiled Romanians in France and Germany. And so, what initially appeared as a playful dreamy image of a cocoon-like room of comfy blankets and warm sunlight now takes on a more loaded significance. The portrayal of this psychic inner world becomes both poetic and heartbreaking. It is an incredibly moving series, the most striking and transfixing aspect of which is the harmonious balance of decay and beauty (sadness and content); the Romanian spirit perseveres. In the Romanian portion of the catalogue, many of the apartments verge on dilapidation, with peeling paint and bleeding wallpaper. Then all of a sudden, there is this explosion of pattern, color and ornamentation, as if life was breathed into the room (this sensation is accentuated by Minda’s focus on light in each of the rooms, which imbues the interiors with a mood of optimism). As you transition into the parts of the book dealing with exile, you begin to realize the full extent of the depressed conditions in which these absentee inhabitants are living. This becomes most apparent in the France section of the catalogue, with some of the rooms recalling the aesthetic of Jeff Wall’s "The Destroyed Room" (1978).

It was an incredibly powerful moment when I realized that the oh-so-pretty cover image (my cozy little imaginary fortress of blankets, light and refuge) actually falls into the latter half of Innenwelt. Here is this utterly inhospitable environment which someone has transformed into a domain of safety and comfort; and in this way I guess it is like a magic fort, it is a refuge. When you read some of the quotes from the exiled individuals, who are either still living in exile or just returning to a profoundly changed Romania, each quote remains full of optimism. Beatrice Minda’s work so beautifully portrays this tension between homelessness and home, sadness and hope. For this reason, I still cannot resist the desire to enter each of the rooms so lovingly depicted in this book.

Hatje Cantz

Clothbound, 10.75 x 10 in. / 160 pgs / 60 color.

| |

|