| RECENT POSTS DATE 12/11/2025 DATE 12/8/2025 DATE 12/3/2025 DATE 11/30/2025 DATE 11/27/2025 DATE 11/24/2025 DATE 11/22/2025 DATE 11/20/2025 DATE 11/18/2025 DATE 11/17/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/14/2025

| | | KYRA SUTTON | DATE 10/9/2015While the media is abuzz with talk of the large Muslim populations in France, Germany, Holland and England, Islam and Italy are terms not often heard in tandem. Italy is, in fact, home to 1.5 million practicing Muslims—a figure that has grown rapidly within the last 10 to 15 years with new waves of immigration from countries such as Albania, Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia and Pakistan, among others. The country, however, contains a mere eight mosques on paper, only one of which holds official state recognition. Though freedom of religious practice without discrimination is enshrined within the Italian constitution, Islam is the second-most widely practiced religion in the country behind Catholicism and it has yet to receive formal recognition from the state. In 2008, a bill was introduced to block the construction of mosques in much of the country, meaning the millions of Muslims in Italy have had to find other spaces in which to gather and pray.

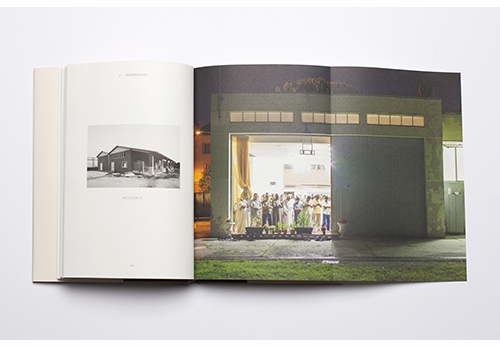

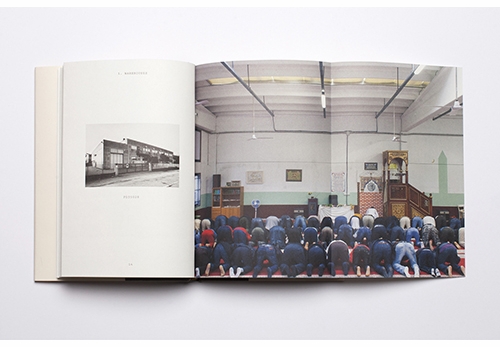

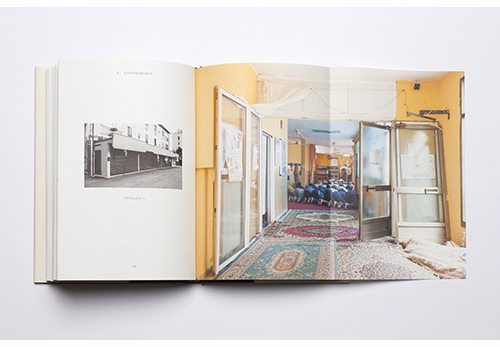

ABOVE and below, mosques inside warehouse spaces.

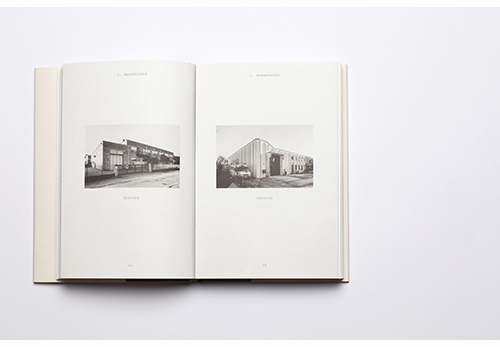

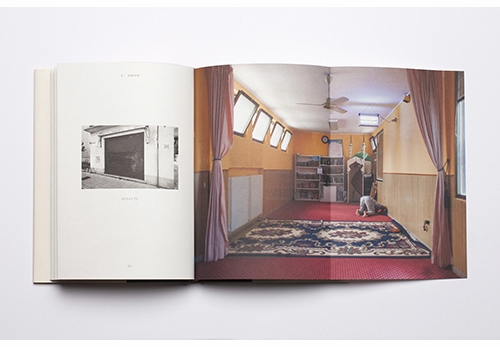

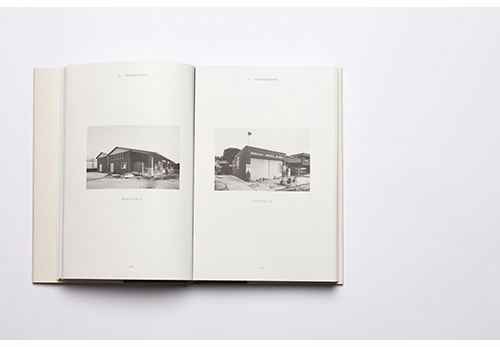

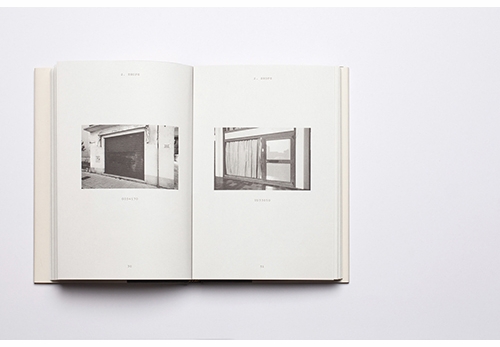

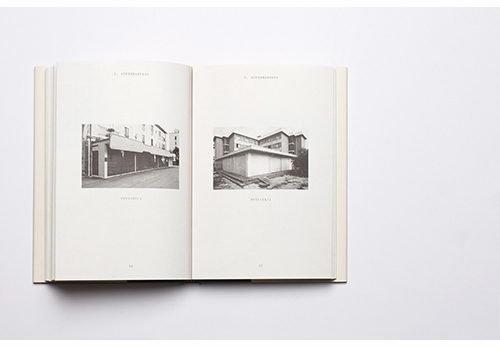

Italian photographer Nicoló Degiorgis' project explores those spaces, homing in on the artist's native Northeast Italy, where the xenophobic Lega Nord party dominates local government. Sorted according to building type—with sections divided by "warehouse," "shop," "supermarket," "apartment," "stadium," "gym," "garage" and "disco"—the photographs of these mosques' exteriors are in black-and-white, free of people and taken diagonally or head on, with the emphasis on the industrial feel of the buildings and their harsh, straight angles; not a dome or minaret is in sight. If you're not paying close attention, it's possible to miss the book's main feature: the photos within the gatefolds, hidden (as in the book's title) beneath these stark, documentary-style images.

The pages open up into two-page full bleed spreads of the prayer spaces; the warehouses and garages appear suddenly expansive and colorful: intricate rugs line floors, with shoes piled up beside them to be retrieved after prayer, and rooms are filled with stacks of Qurans, flat screen TVs and speaker systems. In some of these images we see masses of bodies huddled together in prayer, while others are unpopulated, a lone potted plant the only indicator of a religious community.

Admittedly, this format—outdoor, black-and-white photos outside the gatefolds and indoor, color photos within them—has the potential for heavy-handedness, but the dichotomy works. It feels neither trite nor obvious. Perhaps this is because some of the "interiors" are, in fact, outdoors—in apartment building courtyards or spaces beside warehouses. In a particularly moving image, Degiorgis captures a community mid-prayer as seen through the windows: this is the Islam that is obfuscated, but still visible—if you look for it—to an Italian passerby.

This point-of-view is Hidden Islam's

conceptual hinge: the photographer is not, himself, a practicing Muslim and his images, often shot from behind, as though from a doorway, are from the perspective of an outsider. Indeed, in the spirit of truly immersive documentary photography, Degiorgis negotiated for months to gain acceptance to some of the mosques he photographed, learning of various communities through word of mouth and working to track them down. He has now been to more mosques in Italy than perhaps any other person, Italian Muslims included, and his work of mapping a fragmented, marginalized people—the result of five years of research—is laudable. As Yasman Alipour wrote in her March, 2015 review in the Brooklyn Rail, "the documentary project focuses on a subject of great importance that has so far received little attention: the struggles of Muslims living in the Islamophobic environment of today's Europe."

ABOVE and below, mosques inside shops.

But as noted British photographer Martin Parr writes in his introduction (which, like the interior mosque images, is tucked within a gatefold and therefore possible to miss), "Degiorgis provides a fascinating glimpse of a hidden world and leaves the conclusions about this project entirely in our own hands." Alipour takes issue with this claim, wondering if the images that comprise Hidden Islam are quite as neutral as Parr would have it. Are Degiorgis' photographs part of a classic, simplistic Western depiction of Islam which separates viewer and subject? Do his photographs of bodies bent in prayer with faces obscured present a perspective that is alienating, dehumanizing and "othering?"

It's true that Hidden Islam is intended for a Western audience; the book, published in English, was meant to be shared beyond the Muslim community. But "Western" need not be synonymous with "reductive," and the volume does not succumb to such tropes. Degiorgis' photographs are about stumbling upon the unexpected as an outsider, about an Italy whose landscape is surprisingly similar to that of a country without a storied history of Catholicism—an Italy whose secularism is revealed to be repressive in a way Westerners typically imagine only of far-off places like Saudi Arabia.

ABOVE and below, mosques inside supermarkets.

Some say that all art is political; I would argue that the most politically effective art is rarely so overt. This is what makes Hidden Islam such a success: its content and context are undeniably contentious—as evidenced by the hundreds of reader comments elicited by a 2014 review in The Guardian, which the publisher Rorhof has since turned into another book—but Degiorgis presents his work without comment. Though it resembles a work of literature in design and format, the volume is a photobook in the truest sense. In a time of rampant Islamophobia, and, especially post-Charlie Hebdo, of an Internet saturated with discourse on the topic, it's refreshing and important to encounter a project that affects in a mode beyond the verbal. The images of Hidden Islam—and their thoughtful organization—speak for themselves.

Rorhof

Hbk, 6.5 x 9.5 in. / 90 pgs / 43 color / 84 b&w.

| |

|