| RECENT POSTS DATE 12/11/2025 DATE 12/8/2025 DATE 12/3/2025 DATE 11/30/2025 DATE 11/27/2025 DATE 11/24/2025 DATE 11/22/2025 DATE 11/20/2025 DATE 11/18/2025 DATE 11/17/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/14/2025

| | | THOMAS EVANS | DATE 5/25/2011Until the publication of West and South, the photographer Charles Brittin’s best known work was probably his account of the arrest of the artist Wallace Berman, at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in 1958. This new volume, off press just after Brittin’s death in January of this year, both elucidates and reaches beyond the photographer’s role in the Berman circle, casting him more broadly as the insider chronicler of postwar Los Angeles counterculture, from the mid-1950s to the late 1960s. Pregentrification Venice Beach and its late 1950s assemblagist denizens comprise the “West” portion of the volume, and the African-American civil rights activists of the mid- to late-60s comprise the “South” part. The thematic thread throughout both halves is not only the city of Los Angeles, but the portrayal of those committed to causes that counter prevailing values and laws.

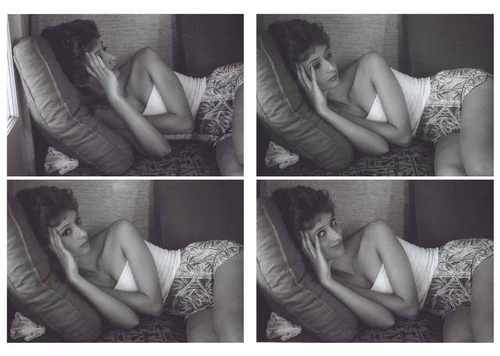

Brittin met Shirley and Wallace Berman in 1953, during Wallace’s earliest assemblage phase and before he had begun Semina magazine. He often described the Bermans as his “family,” and his photographs make this intimacy wonderfully palpable, and in all kinds of ways: we see Shirley posing on a sofa with a knowing, kittenish mischief, or caught in an offhand moment between puffs on a cigarette; we see Dean Stockwell adjusting a garland in Shirley’s hair, on a sunny afternoon in some rural backdrop; or shots of Wallace laying down some sleek moves at a party; or the now classic photos of the family that bespeak the gentle defiance and absolute gracefulness with which they conducted their lives. As West and South’s cover hints, Shirley Berman is the heroine of Brittin’s narrative of the 1950s. Mesmerizingly photogenic, and possessed of a great sense of style in clothing and makeup, she carries herself with an alert and almost regal serenity that comes through in every one of Brittin’s photographs of her.

Among the more overtly iconic images are Brittin’s aforementioned photographs of Wallace Berman’s arrest on charges of exhibiting obscene material at his 1958 Ferus Gallery exhibition—his first, and his last in his lifetime. To give a brief, contextualizing account: the exhibition was composed as an integrated installation of various assemblages, one of which, “Cross,” included a close-up photograph of male and female genitals interlocked. The official story goes that a visitor to Berman’s show lodged a complaint with the police department, although one revelation of this book is Brittin’s suggestion that artist and Ferus co-owner Ed Kienholz may have provoked the arrest as a publicity stunt.

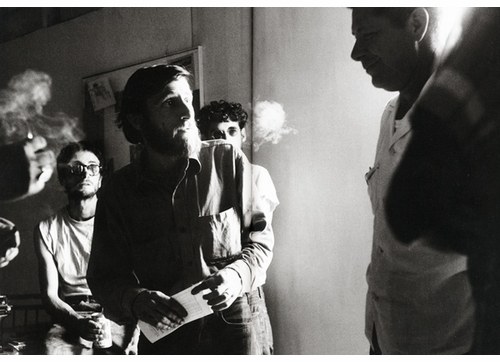

Either way, upon arrival, the police failed to locate the conspicuous offending item and instead seized upon an erotic but not wildly explicit drawing by the occultist and artist Marjorie Cameron, included by Berman in his journal Semina, a copy of which lay inconspicuously inside an assemblage named “Temple.” In what is probably Brittin’s most widely published photograph, Berman is seen inside Ferus, drawing back from but looking querulously towards the arresting officer that looms over him. In the background at the far left sits fellow assemblage artist Wally Hedrick. Berman is bearded, and therefore identified, for the time, as bohemian; the officer is taller, clean-shaven, wearing a white short-sleeved shirt that looks unnervingly immaculate in this context, and is sporting a malevolent grin (or if not malevolent, then certainly no-one else is smiling).This photograph truly captures the terrifying censoriousness of 1950s America, Los Angeles in particular. Kristine McKenna has written elsewhere of how, “in 1951 the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors made it illegal to exhibit modern art in the city of L.A. on the grounds that modernism was a front for communist infiltration”—a legal excess that conveys how daring a venture Ferus must have been in such an arid climate, and how daring the Bermans were in their art and lives.

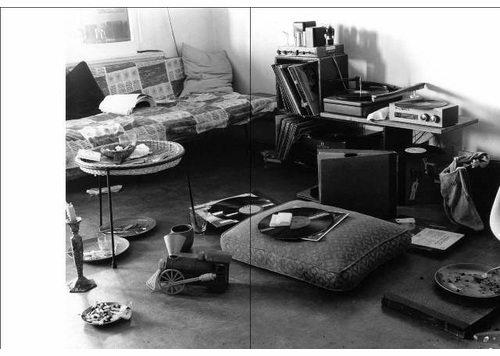

But intimacy is the dominant tenor of the “West” section of West and South: intimacy and a pleasure in community cherished and nourished. Looking at Brittin’s record of the period, one wonders whether Berman made Semina in part to picture this community and its patron saints to himself and others, as a life stance. Berman and his friends worked insistently in a context of their own making (poet Robert Duncan wrote that "Berman's very art is the art of context”).Ironically, one instance of this intimate, or ‘in the trenches’ feel of Brittin’s photographs portrays no people at all, but rather the aftermath of people—an image of Brittin’s Venice apartment the morning after a party. Overflowing ashtrays and records loose from their sleeves are familiar enough fare for such a subject; perhaps what’s curious about this picture is actually the relative tidiness of the room, suggesting that perhaps music and dancing rather than drinking and overdosing was the focus of the evening.

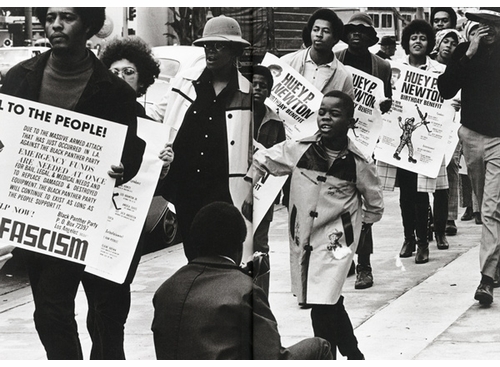

In 1962 Brittin and his wife Barbara began to work for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). By 1965 they had become active supporters of the Black Panthers, and Brittin documented their rallies in Los Angeles and (occasionally) elsewhere. The “South” portion of this book is devoted to this later phase in Brittin’s photography, which also marks a shift away from aspects of his earlier bohemianism: “at that point I began to drift away from the people I’d been close to in the fifties,” he writes in West and South’s introduction. “None of them had strong feelings about the political issues of the time, and once Barbara and I became politically active we knew we were under surveillance. Seeing a lot of our friends, many of whom were involved with drugs, would’ve jeopardized them as well as us.”

Brittin’s civil rights photographs include portraits of Panthers Bobby Seale and Kathleen Cleaver, and various CORE and Panther demonstrations and protests attended by the Brittins throughout the 1960s. The electrical tension of these times permeates this section of the book, and underscores its portrait of Los Angeles as a hotbed of several countercultural strains at once. West and South is full of images that span the most ordinary and the most extreme moments in these cultures, and anchor their endeavours to a tangible human scale.

Hatje Cantz

Hbk, 9.5 x 13 in. / 216 pgs / 150 duotone.

| |

|