| RECENT POSTS DATE 12/11/2025 DATE 12/8/2025 DATE 12/3/2025 DATE 11/30/2025 DATE 11/27/2025 DATE 11/24/2025 DATE 11/22/2025 DATE 11/20/2025 DATE 11/18/2025 DATE 11/17/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/14/2025

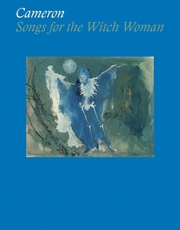

| | | HAYDEN ANDERSON | DATE 3/13/2015In her introduction to Cameron: Songs for the Witch Woman, curator Yael Lipschutz writes that, "Cameron's commitment to live her life as art itself constitutes a rare, avant-gardist approach, one that makes separating her biography from the thousands of drawings, paintings and sketchbooks she left behind a near impossibility." Luckily for us, her biography is as fascinating as they come.

ABOVE: An undated portrait of Cameron by George Herms. Unless noted, all images are reproduced from Cameron: Songs for the Witch Woman.

Born Marjorie Cameron in 1922, Cameron grew up in rural Iowa before embarking upon a brief stint in the Navy during the Second World War. Following her service, she moved to Pasadena, where her family had relocated. There, Cameron threw herself into the jazz world bohemia surrounding the clubs on South Central Avenue in Los Angeles. Soon after, she would discover another subcultural undercurrent of L.A.—one that was smaller and stranger, and which would radically alter the course of her life. One fateful evening in 1945 or 46, Cameron attended a party at a Pasadena mansion dubbed The Parsonage, home of the rocket engineer and occultist Jack Parsons. Immediately entranced by Cameron's red hair, Parsons believed that she was the "Scarlet Woman" that he had been trying to conjure through ritual magic. The two began an intense love affair, during which Parsons introduced Cameron to the esoteric philosophies and practices of astrology, the Tarot, I Ching and Aleister Crowley's occult Thelema, mentoring her in rituals of "sexual magick."

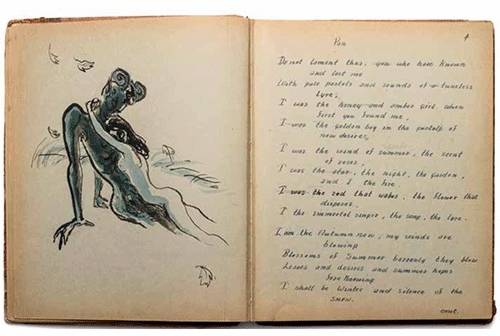

Cameron used her artwork as a site to explore the new ideas she was encountering through Parsons, evident in a series of watercolor drawings titled Songs for the Witch Woman, created in response to a series of Parsons' poems. Published to accompany MOCA LA's 2014 exhibition at the Pacific Design Center, the engrossing monograph Cameron: Songs for the Witch Woman opens with scanned pages from the Parsons/Cameron collaboration. The left pages feature Cameron's drawings of female figures, fantastical creatures and eerie landscapes, while Parsons' handwritten verse poems, featuring titles like Pan, Danse and Sorcerer appear on the right.

ABOVE: The "Pan" spread from Cameron and Jack Parsons' Songs for the Witch Woman, 1951.

Although Cameron would always return to California, her life thereafter was marked by several long and restless sojourns. After marrying Parsons, Cameron traveled to Europe, where she tried and failed to locate Aleister Crowley, who had died. She then traveled to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, where she met a community of artists that included Leonora Carrington and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

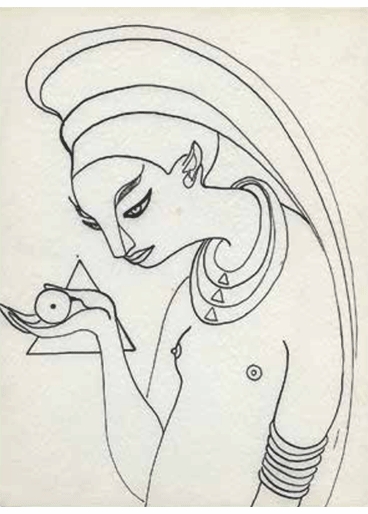

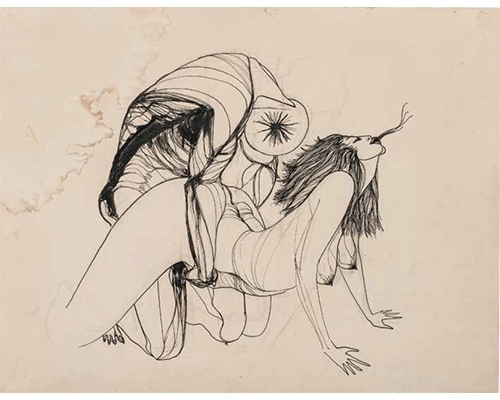

But tragedy caught up to Cameron in 1952, when Parsons was killed in an explosion at his laboratory. Devastated, Cameron retreated to the desert town of Beaumont, California, where she immersed herself in magical practices, claiming to have created a mystical child—or "wormwood star"—with the spirit of Parsons. She also continued working on her Songs for the Witch Woman series, this time in black-and-white ink.

ABOVE: "Witch Woman," 1955.

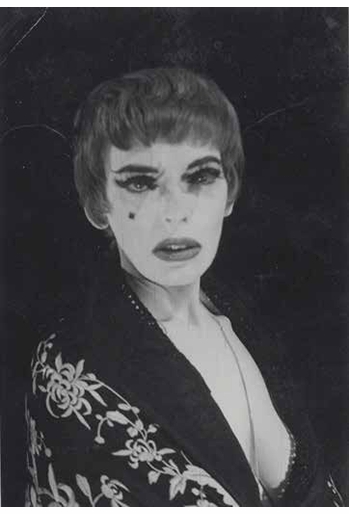

When Cameron finally emerged from her solitude, she returned to L.A. and fell into contact with some of the era's most influential avant-garde artists and counterculture figures. She first gained notoriety through her acting, which included a starring role in Kenneth Anger's film Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome and an appearance alongside Dennis Hopper in Curtis Harrington's Night Tide.

ABOVE: Cameron as the Scarlet Woman in Kenneth Anger’s 1956 film, Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, photographer unknown.

Cameron's attempts at expanding her consciousness did not end when she returned to the city, and as before, this process was documented in her work. In 1955, in the midst of a peyote trip, she created a drawing that would have repercussions for the greater L.A. art scene. A bold depiction of interwoven mysticism and sexuality, Peyote Vision depicts a woman having sex with an alien figure. The drawing was later displayed in the window of the esoteric bookstore Books 55, where it was seen by the artist Wallace Berman. Berman was so entranced by the work that he sought the woman who made it.

ABOVE: “Peyote Vision," 1955.

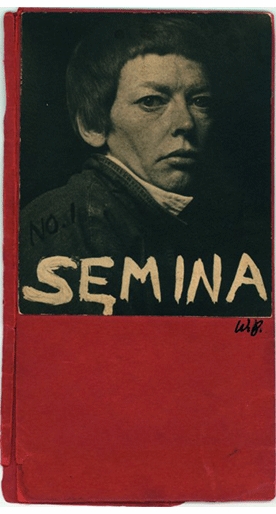

Berman, subject of the recently reprinted classic, Semina Culture: Wallace Berman and His Circle, was a central figure in the California Beat art scene of the late fifties. A man of eclectic interests ranging from Kabbalah to jazz to French literature, Berman attracted and sustained a network of visual artists, poets, filmmakers and photographers. Integral to this network was Berman's hand-printed publication, Semina, which extended his assemblage technique by including texts by William Blake and Charles Baudelaire alongside the work of friends like Allen Ginsberg, Llyn Foulkes and Michael McClure. Berman had such a high regard for Cameron that he featured her portrait on the cover of the very first issue of Semina (1955), which included a reproduction of Peyote Vision inside. When Berman staged his first and only gallery exhibition two years later at Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, he included Peyote Vision in one of his assemblages.

ABOVE: The first issue of Semina, featuring Berman's portrait of Cameron. Image is reproduced from Semina Culture.

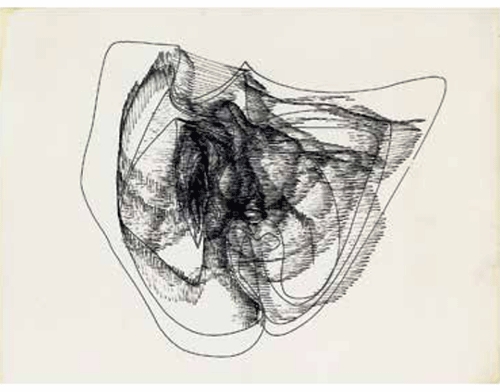

But not everyone was so appreciative; a visitor to Berman's Ferus show found Cameron's drawing offensive and called the L.A. Vice Squad, anonymously alleging public obscenity. As a result, the show was raided during the opening and shut down; Berman was later convicted for the display of lewd and obscene materials. This infamous incident would have a profound effect on both Berman and Cameron, neither of whom would consent to show their work in a gallery context again in their lifetime. And yet, both would continue to work prolifically, as is evident in the second half of Songs for the Witch Woman—especially the series of ink drawings, Pluto Transiting the Twelfth House.

ABOVE: A drawing from Cameron's Pluto Transiting the Twelfth House series, 1978–86.

That neither Cameron nor Berman's artistic output was affected by the rejection of the gallery system is not surprising, given the intensely personal nature of their work. Just as Michael Duncan's introduction to Semina Culture describes the art of the Beat movement as "one that stands outside of the traditional art-historical narrative of 'progression,'" the only progression that Cameron's art followed was that of her own spirit as she dove ever deeper into the investigation of self. Songs for the Witch Woman gathers the traces left from that journey, which, thankfully, opens up the world of Cameron for us just a little bit more, mystery still intact.

HAYDEN ANDERSON studied media and literature at New York University. He is Associate Publicist at ARTBOOK | D.A.P.

Cameron-Parsons Foundation/the museum of contemporary art, los angeles

Hbk, 9.25 x 11.75 in. / 88 pgs / 75 color.

| |

|