| RECENT POSTS DATE 12/11/2025 DATE 12/8/2025 DATE 12/3/2025 DATE 11/30/2025 DATE 11/27/2025 DATE 11/24/2025 DATE 11/22/2025 DATE 11/20/2025 DATE 11/18/2025 DATE 11/17/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/14/2025

| | | MADELINE WEISBURG | DATE 12/4/2015Experimental filmmaker, musicologist, artist, ethnographer and occultist Harry Smith (1923-1991) was a key member of the Beat avant-garde. He was also a lifelong collector who gathered idiosyncratic objects as varied as paper airplanes, string figures, tarot cards and Ukrainian Easter eggs, many of which are housed at the Anthology Film Archives, where John Klacsmann & Andrew Lampert are currently editing a remarkable series of catalogue raisonnés co-published by Anthology and J & L Books. Madeline Weisburg sat down to speak with them about the two new volumes, documenting Smith's Paper Airplane and String Figure collections.

MADELINE WEISBURG: Can you describe Harry Smith's relationship to the Anthology Film Archives?

JOHN KLACSMANN: Harry Smith is a foundational artist in the Anthology Film Archives collection in terms of the acquisition of his films early on and our archiving of not only his films, but also other ancillary materials. One of his films, FILM NO. 11: MIRROR ANIMATIONS, was part of Anthology’s very first screening on November 30, 1970. Most recently we’ve been working on digitizing his field recordings and audio tapes, many of which include his very interesting phone conversations from the late 1970s. Furthermore, Anthology holds a collection Harry’s art—his paintings, and some other collections of his like tarot cards, toys, and various research index cards. We even have a tree stump that belonged to him.

ANDREW LAMPERT: His relationship to Anthology dates back to before we opened in 1970. Jonas Mekas, our founder, was a major advocate of Harry and did a lot starting in the early ‘60s to make his experimental films prominent. He discovered them via Allen Ginsberg, who met Harry by chance one night at the Five Spot Jazz Club. So Anthology and Harry Smith have this sort of simpatico, long term, familial relationship.

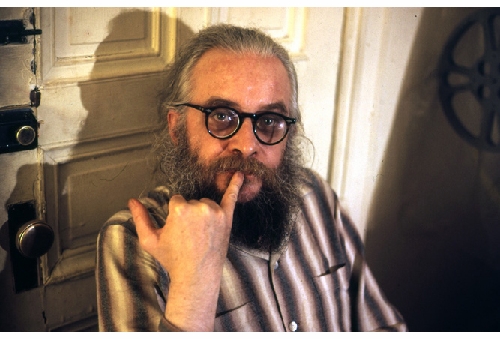

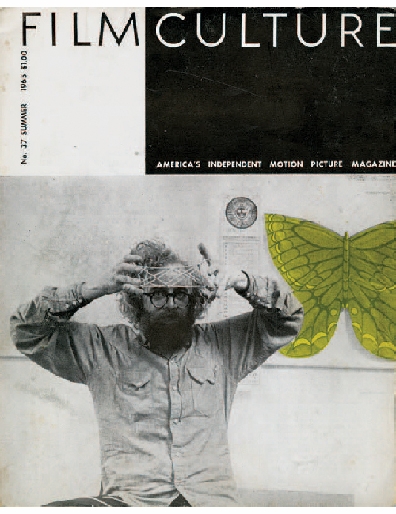

ABOVE: Harry Smith, c. 1972.

MW: How did Anthology get involved with Harry’s non-film archive?

AL: Via Harry himself. When he died in 1991, Anthology was just one of many repositories for his things. Harry had a way of leaving or gifting collections to friends and colleagues. These are the ones that actually survived. A lot of stuff got lost in his lifetime due to inattention or his own self-destructive ways. When he didn’t pay his landlord at a hotel or low-rent apartment things would just get thrown away. He’d experience manic episodes where he’d just destroy entire bodies of work and presumably collections of objects that he had gathered over the years. We have tight-knit relationships with many artists, so we archive a lot of things that are not technically film—materials that inform the films in a distinct way. Harry was a polymath—a musicologist doing field recordings, a student of alchemy, all these other things—so while his collections are disparate and weird, when you look at the films you can really start to see how they all dovetail together.

MW: Traditionally, the term catalogue raisonné refers specifically to a complete compilation of an artist's body of work. But with this project you are presenting Harry Smith’s found object collections as a catalogue raisonné in itself. What made you decide to frame the project this way?

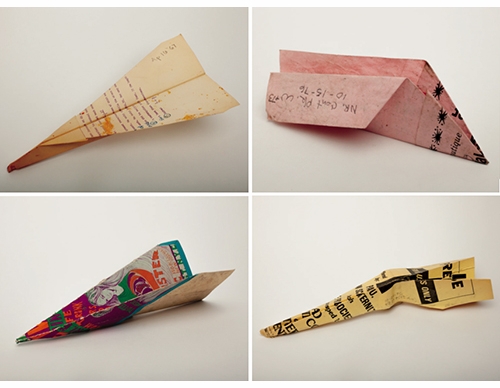

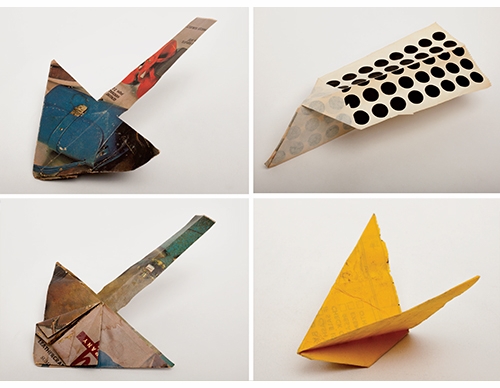

JK: One thinks of a catalogue raisonné as being definitive and complete. As we discuss in the books' introductions, we will never have a complete understanding or index of all of Harry Smith's activities. At the same time, we also assigned each object a number and indexed them as best we could. From what we can tell, Harry's collection of found paper airplanes is the largest in existence. We show the 251 that survived in the book, but he probably collected far more.

AL: It's tongue in cheek in many ways. With Harry, every story leads to more mystery. Even the people who were closest to him him never knew in any deep way about these undertakings. Rosebud, his "spiritual wife," said that when Harry started talking you just couldn't understand what he was talking about. The guy was a mile a minute. There's that largess of a character that can't be tied down. My hope is that someone will see these books and go, 'oh I have some of those,' and suddenly 250 more airplanes will pop up.

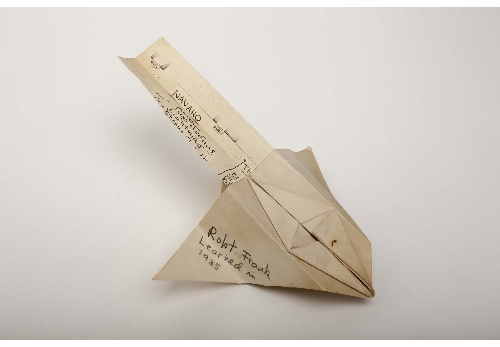

ABOVE: Paper airplanes found around New York City, 1967-1976.

MW: I could see lots of people coming out of the woodwork. Harry Smith knew so many types of people, and he remains appealing to so many different audiences.

AL: That's why we didn't put his name on the cover, just on the spine and back. When it's sitting on the table at Spoonbill & Sugartown or Mast Books, some people will pick it up because they see the name "Harry Smith." But if somebody just sees that paper airplane or that beautiful string figure and then looks at the back and has no clue about folk music, experimental film or the occult, then they're facing this amazing collection of objects and research.

The types of people who appreciate Harry Smith are intriguingly as splintered as his personality. He made a mark across a wide field of people, not just filmmakers. In retrospect, it's clear that he was a major figure, but in his lifetime he lived like a vagrant. That's such an interesting legacy for someone who lived on the fringes, crippled by his inability to live in the mainstream.

JK: One point of the books is to make the collections accessible. We want to share this material with an audience, not necessarily to demystify it, but to help flush it out. I think the covers speak to this sort of peering into a cabinet of curiosities.

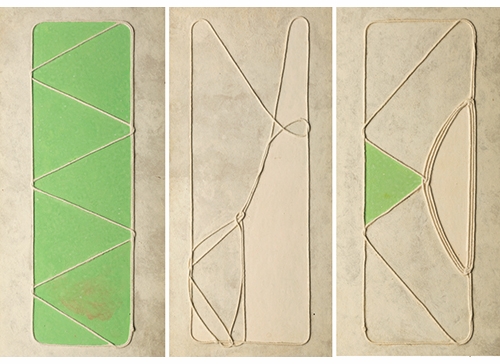

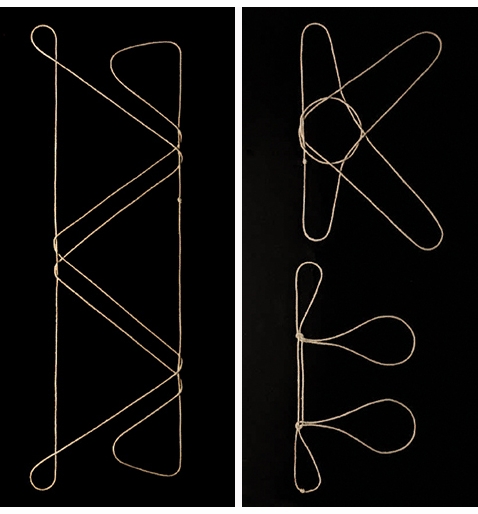

ABOVE: String figures from the Anthology Film Archive's collection.

MW: Absolutely, the range of his activities was extraordinary. Such an output was by no means typical of midcentury artists, but Smith was not a conventional artist. Did he see collecting as an extension of his creative work?

AL: Certainly one can make a holistic connection between these activities. As a teen he was an amateur anthropologist and spent time documenting the dialects of different tribes in the Pacific Northwest. Projects like the Anthology of American Folk Music are these strange things where there's a creative aspect, but they’re also really about research.

JK: His collecting activities appear within his other work, so I think it's very hard to separate the two. Whether he was making art or collecting things it was all just integrated into his unusual lifestyle.

AL: In today's contemporary art lexicon we talk a lot about artists engaging with the archive. I don't really see Harry's work falling into that mode at all.

JK: Harry's interests were more anthropological. Lots of his collections are a little more traditional in that way, whether they are sting figures, Ukrainian Easter eggs or Seminole patchworks to be used in quilts. It's more folk craft related, as opposed to another kind of investigation.

ABOVE: Harry Smith with a string figure on the cover of Film Culture, 1965.

MW: I love that he was doing this idiosyncratic, meaningful anthropological research completely outside of academia. What were his thoughts on the institutionalized or mainstream discipline of anthropology? I’m wondering if he ever engaged with academics, or if he was interested in traditional repositories for cultural artifacts—like natural history museums or libraries?

AL: Most of his research was done at the library. The New York Public Library was central to his string figure research. When you read interviews, he’s always referencing then-contemporary journals within various academic fields. He was up to date on French theory and talked a lot about Claude Levi-Strauss. All of his pursuits were approached with the rigor of academia, but without any of the restrictions. I think his interests in art, music and drugs set him apart.

MW: How did Harry start a new collection?

JK: We don't really know, but we hypothesize that he was interested in patterns, as in the string figures. He was very interested in trying to find universal patterns, particularly in how they might relate to the ways that generations share and pass down craft traditions and information.

ABOVE: Mounted string figures from the collection of musician and photographer, John Cohen.

MW: I like a quote that you use in the book, where Harry calls the string figures “…the only universal thing other than singing.”

JK: He wasn't the first person to study string figures and to try to find universal connections, but that was certainly his interest. He wanted to link different cultures together.

AL: This brings me to the sequencing of the Anthology of American Folk Music, which is divided into ballads, social music and songs. Harry created categories, but as you're listening to these records, you can go from a cowboy ballad to a Scottish ballad to a blues song. As a listener you may not be able to recognize the cultural origins of a song, or the specific performer. Harry created categories through sequencing, so that all of sudden corollary relationships could start happening between individual songs and works. As a listener, it's more a lived experience than an intellectualized experience. When you look at his intentions with his various pursuits and collections, that sequencing, editing, that idea of blurring the line, is important.

ABOVE: A still from Smith's complex Film #18: Mahagonny (1970–1980), which prominently features string figures.

MW: Can you talk about the different ways that he categorized the paper airplanes and string figures?

AL: The majority of the string figures have no indicators as to what they are: when you look at them, they're very much aestheticized versions of what they might be in one's hand. Looking at the string figures, it seems to be a project that was so large that he maybe couldn't figure out how to encapsulate it. The notes that exist are quiet fragmentary.

JK: He didn't really categorize the airplanes outside of when and where he found them, which for the majority of the time he noted on the physical airplanes. We made a map that plots this in the book. Then there's another category of planes, which are the ones he asked people to make for him. In the book, there's one attributed to Robert Frank. On some he also noted the age of the person when they learned how to make paper airplanes.

ABOVE: A paper airplane attributed to Robert Frank, who doesn't recall making it for Smith. The paper used comes from a photocopy of Smith's notes on string figures.

MW: I don’t think I’ve ever noticed a paper airplane on the street in New York. Do you ever spot them?

JK: When we were thinking about the book we wondered if paper airplanes were more popular years ago. We never used to notice them. But since we started working on the book we've become aware.

AL: Not only have we seen them, but Jason Fulford, who published the book and took the photographs, found some on Harry's birthday! I've found a few, and recently my three-year-old daughter came home from school with a paper airplane that she made. I couldn't believe it. While working on press in Korea, Jason sent photos of the staff making airplanes out of the uncut pages of the book.

JK: Maybe paper airplanes are more present than we realize.

AL: That's the magic with Harry. By having his antennas so finely tuned, he shows the rest of us what we've not been able to see right in front of our face.

JOHN KLACSMANN is Archivist at Anthology Film Archives in New York City where he preserves artist cinema. In the past he has worked as: a fireworks salesman, a computer programmer, a Class-D FM radio DJ, a Technicolor archivist, and a film laboratory technician. He currently runs a tiny tape label, ZAP Cassettes, volunteers as a 16mm projectionist at Spectacle Theater in Brooklyn, and is a contributing editor to INCITE: Journal of Experimental Media.

ANDREW LAMPERT is a filmmaker/artist whose moving image, photography and performance pieces are regularly presented in venues big and small throughout North America and beyond. In late 2015 he stepped down from his position as Curator of Collections at New York City's Anthology Film Archives where he spent 17 years preserving and programming films and videos. He has taught at Purchase College and the New School, recently co-edited two books on the paper airplane and string figure collections of Harry Smith for J&L Books, and also edited THE GEORGE KUCHAR READER in 2014 for the press Primary Information. Lampert is currently engaged in a number of projects, including a one-man multimedia show titled Beuys Block that thoroughly documents his deep antipathy towards Joseph Beuys.

J&L Books/Anthology Film Archives

Pbk, 6 x 9 in. / 240 pgs / 300 color. $35.00 free shipping | |

|